Foodborne illness (also called foodborne disease and informally referred to as food poisoning) refers to human sickness or disease caused by consuming food or beverages contaminated with harmful biological, chemical, or physical hazards.

Foodborne illness is a common – yet preventable – public health problem. Ensuring food safety is increasingly more important as food trends change along with the globalization of our food supply. As our food supply becomes increasingly globalized, the need to strengthen food safety systems in and between all countries is becoming more and more evident.

To prevent foodborne illness, it is necessary to understand how food becomes unsafe to eat and what proactive measures can be taken.

How many people are affected by foodborne illness each year?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that each year – 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) become ill, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die from contaminated foods or beverages. [1]

What are the main causes of foodborne illness?

The CDC states that foodborne infections in the U.S. are most commonly caused by viruses (59%), bacteria (39%), and parasites (2%). [2]

Among these pathogens (microorganisms that can produce disease), the top five that cause the most foodborne illnesses in the U.S. are: [3]

- Norovirus

- Salmonella

- Clostridium perfringens

- Campylobacter

- Staphylococcus aureus (Staph)

Some other pathogens don’t cause as many illnesses, but they are more likely to lead to hospitalization and fatal infections. They are:

- Clostridium botulinum (botulism)

- Listeria

- Escherichia coli (E. coli)

- Vibrio

What is the economic impact of foodborne illness?

Knowing the economic burden of foodborne illness—the impact on the welfare of all individuals in a society—can help public health officials and food industry better mobilize food safety resources.

In terms of economics costs, the USDA estimates that foodborne illnesses cost more than $15.6 billion each year (inpatient medical care, outpatient expenses, lost wages, and continued evaluation of foodborne infections). [4]

- Learn about foodborne hazards and pathogens, cross contamination, temperature controls, cleaning and sanitation methods, and the best practices to prevent foodborne illnesses.

- Food Manager ANSI Certification: SALE $99.00

- Food Handler ANSI Training for only $7.00!

- Enter Promo "train10off" at Checkout

What are the types of foodborne illness?

Foodborne illnesses can be categorized by the type of illness: [5]

- Infection: A foodborne infection is caused by eating food contaminated pathogenic (harmful) microorganisms – such as bacteria, parasites, or viruses – which invade and multiply in the intestinal tract or other tissues – and cause illness. Bacteria causing infections include Salmonellosis and Listerosis. Viruses include Hepatitis A, and norovirus. Parasites include Trichinella and Anisakis.

- Intoxication: Foodborne intoxication is caused by consuming food containing either poisonous chemicals or toxins produced by microorganisms in the food. Poisonous chemicals causing illness are substances such as cleaning compounds, sanitizers, pesticides, and heavy metals. Examples of toxin producing bacteria include Clostridium botulinum, Staphylococcus aureus, and Clostridium perfringens. Toxins are also the natural part of some plants and mushrooms. Seafood toxins include ciguatera and scombroid.

- Toxin-mediated infection: Foodborne toxin-mediated infections are the result of eating food containing harmful microorganisms which produce toxins while in the intestinal tract. Viruses and parasites do not cause toxin-mediated infections. Bacteria such as Shigella and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli cause toxin-mediated infections.

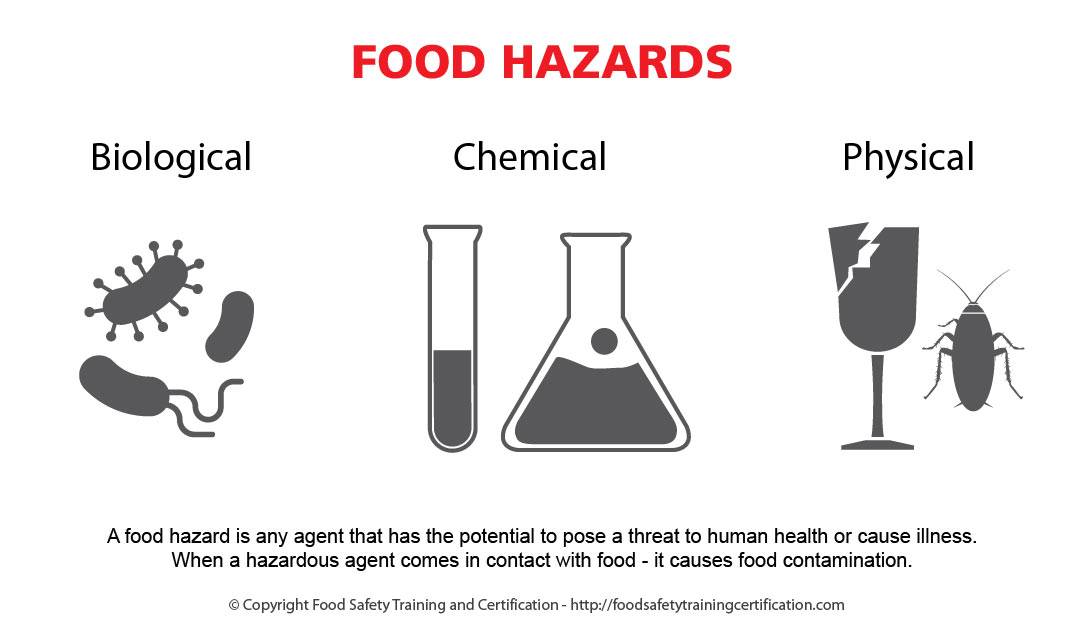

Food Hazards

A food hazard is any agent that has the potential to pose a threat to human health or cause illness. When a hazardous agent comes in contact with food – it causes food contamination.

Food hazards are generally classified by their sources:

- Biological Hazards: Biological hazards include bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Bacteria and viruses are responsible for most foodborne illnesses and are the biggest threat to food safety.

- Chemical Hazards: Chemical hazards include natural toxins and chemical contaminants (cleaning and sanitizing agents, natural toxins, drugs, food additives, pesticides, industrial chemicals, and other toxins).

- Allergens: Food allergens are a sub-category of natural toxins within chemical hazards. Some people are sensitive to certain proteins in foods. The 8 major food allergens include: milk, eggs, fish, crustacean shellfish (lobster, crab, shrimp), wheat, soy, peanuts, and tree nuts.

- Physical Hazards: Physical hazards are foreign objects which include glass, metal, plastic, bone chips, hair, insects, pest droppings, and other undesirable particles or objects.

Bacteria Growth and Food

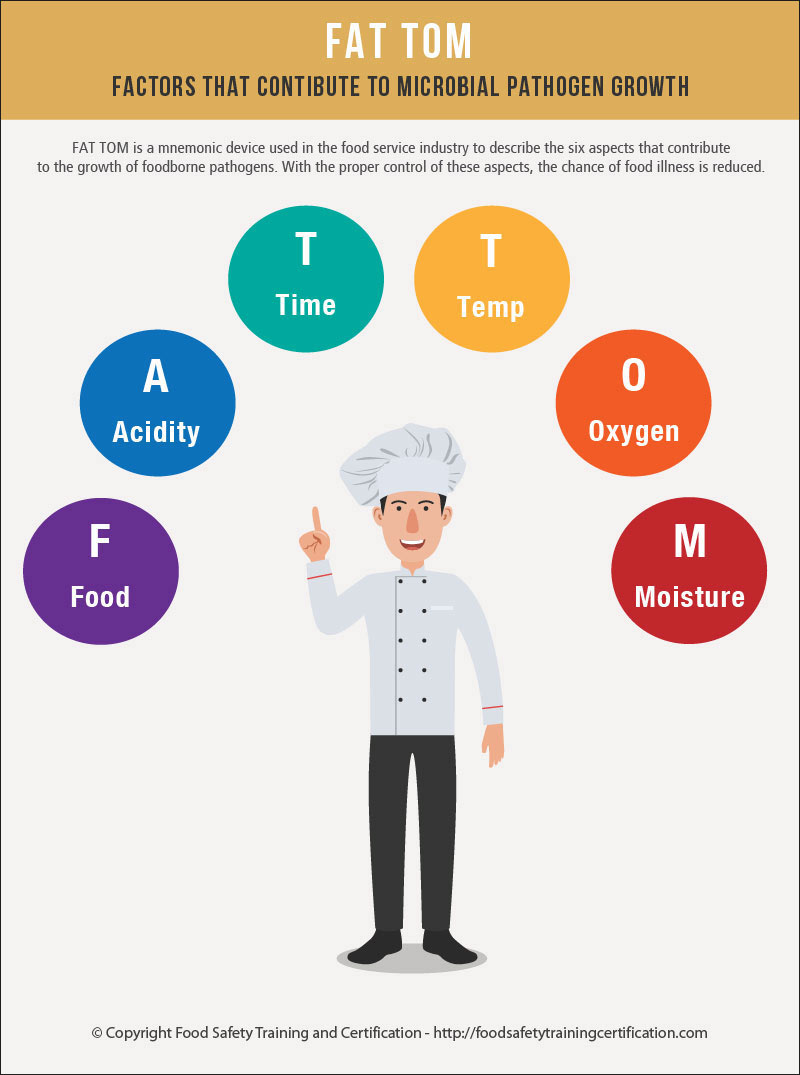

Given the right conditions, millions of bacteria can grow on common, everyday foods. These conditions are:

- Time and temperature: Bacteria grow most rapidly in the range of temperatures between 40 °F and 140 °F, doubling in number in as little as 20 minutes. This range of temperatures is often called the “Danger Zone.” So, it’s important not to keep food at this temperature for too long.

- Oxygen: Most bacteria require air to survive, these are called aerobic bacteria. Although some bacteria – called anaerobic bacteria – can survive without oxygen. Which is why it’s still possible to get food poisoning from canned food items.

- Food: Bacteria need a constant source of food to survive, especially protein. High protein foods such as meat are particularly vulnerable to biological contamination from bacteria, which means they’re considered high-risk foods. High-risk foods that bacteria love best include dairy products, meat, poultry, fish and shellfish

- Water: Water is essential to bacterial growth and without it, most bacteria will die. Which is why drying foods as a way of preservation are so effective and have been performed for thousands of years. This includes moisture in ‘wet’ foods such as juicy meats, sandwich fillings, soups, sauces and dressings.

- PH Levels: PH refers to food acidity and is measured on a scale of 1 (acidic) to 14 (alkaline). Most fruits generally have a PH level of between 1 – 5.9, so are considered acidic. While many alkaline foods such as vegetables have a PH level at the other end of the scale. Bacteria thrive in neutral foods that are neither acidic or alkaline and generally have a PH level of between 6 – 8.9. Foods such as meat and seafood are prime examples of neutral foods.

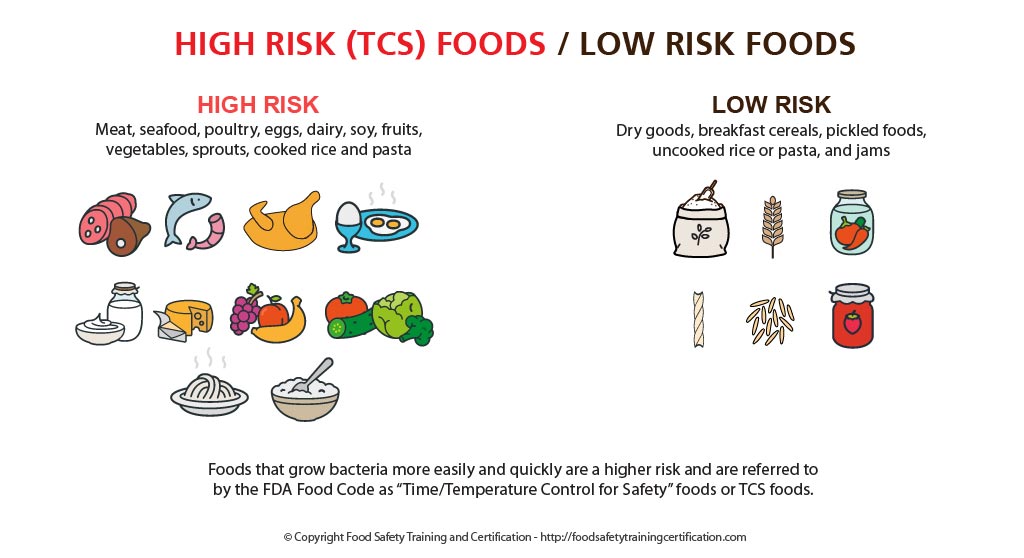

High Risk/Low Risk Foods for Bacterial Growth

High-risk foods are those that have ideal conditions for bacterial growth. This means they’re usually:

- Neutral in acidity

- High in starch or protein

- Moist

Examples: Foods such as raw meat or seafood, cooked rice or pasta, eggs, and dairy are all considered high-risk because they provide the perfect environment for bacteria to grow. This is why it’s essential to practice proper food handling when dealing with these foods.

Low-risk foods are those that don’t have particularly good bacterial growth conditions. These foods are:

- High in acidity

- High in salt or sugar

- Dried

- Canned or vacuum packed

Examples: Low-risk foods like dry goods, breakfast cereals, pickled foods, uncooked rice or pasta, and jams. Although these foods are not common sources of biological contamination, the appropriate care must still be taken when handling them.

Symptoms of Foodborne Illness

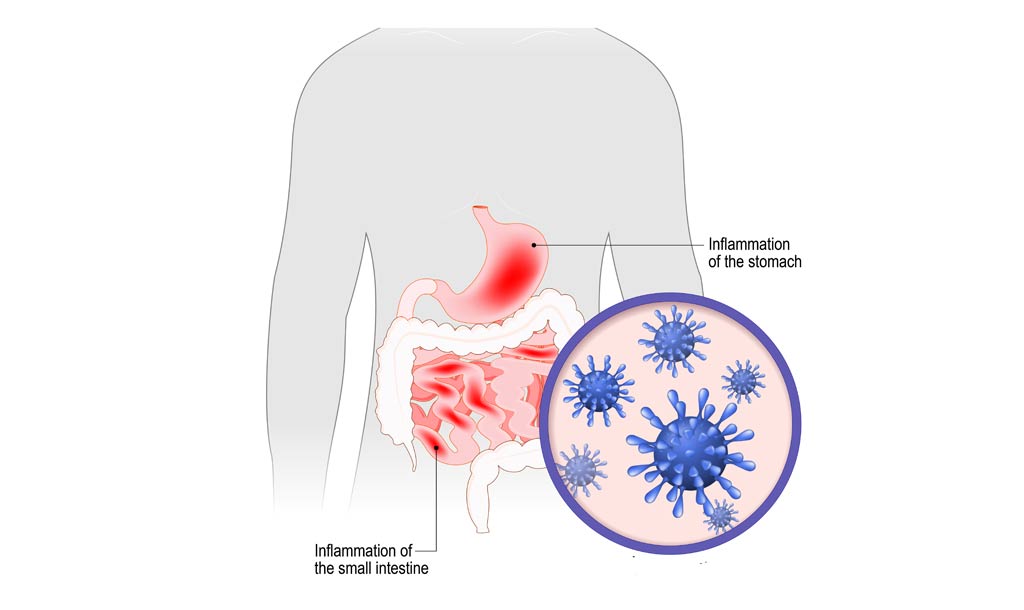

- Common symptoms of foodborne illness are diarrhea and/or vomiting, typically lasting 1 to 7 days. Other symptoms might include abdominal cramps, nausea, fever, joint/back aches, and fatigue.

- What some people call the “stomach flu” may actually be a foodborne illness caused by a pathogen (i.e., virus, bacteria, or parasite) in contaminated food or drink.

- The incubation period (the time between exposure to the pathogen and onset of symptoms) can range from several hours to 1 week.

At Risk Groups for Foodborne Illness

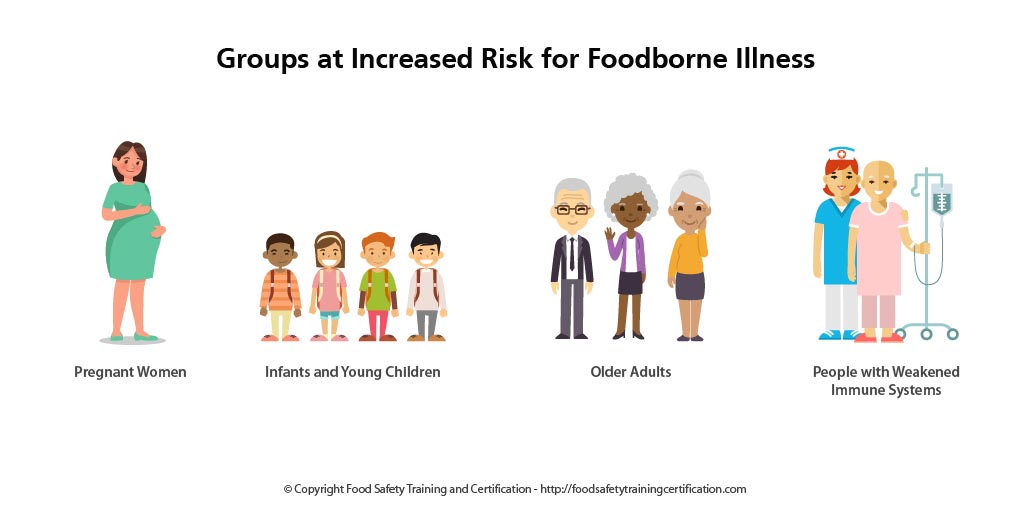

Foodborne illness can affect anyone who eats contaminated food. However, certain populations are more susceptible to becoming ill with a greater severity of illness. These groups include:

- Pregnant women;

- Infants and young children;

- Older adults;

- People taking certain kinds of medications or with immune systems weakened from medical conditions, such as diabetes, liver disease, kidney disease, organ transplants, HIV/AIDS, or from receiving chemotherapy or radiation treatment.

Most people with a foodborne illness get better without medical treatment, but people with severe symptoms should see their doctor.

These vulnerable groups should take extra precautions and avoid the following foods:

- Raw or rare meat and poultry;

- Raw or undercooked fish or shellfish;

- Raw or undercooked eggs or foods containing them ( cookie dough and homemade ice cream);

- Fresh sprouts;

- Unpasteurized ciders or juices;

- Unpasteurized milk and milk products;

- Uncooked hot dogs.

Summary

It is very important to understand what, why, and how foods can make you sick, but more importantly, the food safe principles and procedures to prevent foodborne illnesses.

References

[1]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Burden of Foodborne Illness: Findings. Retrieved June 10, 2019, from

https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/2011-foodborne-estimates.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimates of Foodborne Illness in the United States. Retrieved June 10, 2019, from

https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Attribution of Foodborne Illness: Findings. Retrieved June 10, 2019, from

https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/attribution/attribution-1998-2008.html

[2]

Emerging Infectious Diseases – January 2011; Vol 17 (1), pp. 7-20. Retrieved June 10, 2019, from

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/content/17/1/pdfs/v17-n1.pdf

[3]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Foodborne Illnesses and Germs. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from

https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/foodborne-germs.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Study: Attribution of Foodborne Illness in the U.S. 1998-2008. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from

https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/attribution/attribution-1998-2008.html

[4]

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) – Economic Research Center (ERS). Quantifying the Impacts of Foodborne Illnesses. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from

https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2015/september/quantifying-the-impacts-of-foodborne-illnesses/

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) – Economic Research Center (ERS). Cost Estimates of Foodborne Illnesses. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from

https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/cost-estimates-of-foodborne-illnesses/

[5]

University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Institute of Agriculture and natural Resources. Food Poisoning (Foodborne Illness). Retrieved 23:38, July 7, 2019, from

https://food.unl.edu/food-poisoning-foodborne-illness

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Foodborne Illnesses. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/foodborne-illnesses

Minnesota Department of Health. Causes and Symptoms of Foodborne Illness. Retrieved June 10, 2019, from

https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/foodborne/basics.html

Wikipedia contributors. (2019, June 23). Foodborne illness. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 7, 2019, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Foodborne_illness&oldid=903114088

National Capital Poison Center. Food Poisoning. Retrieved July 7, 2019, from

https://www.poison.org/articles/2013-apr/food-poisoning

The Bad Bug Book (2nd Edition). U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition (2012). p.1.

https://www.fda.gov/media/83271/download